Posts com a tag: lang

Irish nouniness

2020-04-10 23:21 +0100. Tags: lang, in-english

At work, when we make changes to some code, we make a pull request and send the link for others to review the changes, usually accompanied by a message such as "Can you review?", "Please review", or other variations depending on how inspired we are feeling on each particular occasion. A couple of weeks ago, I considered sending the message in Irish just for fun. I barely know any Irish, though, so I resorted to Google Translate. Upon entering the supposedly simple sentence "Can you review?" into it, however, I was confronted with the following translation:

An féidir leat athbhreithniú a dhéanamh?

And I was twice perplexed. At first, I was surprised because I got more words than I was expecting to get back. But the more I stared at this sentence, the more perplexed I got, for a different reason: I couldn't identify the verbs in it, at least not in the form and places I expected to see them.

Let's go through this sentence in order. 'An' is, among other things, an interrogative particle. Usually the verb is the first thing in the sentence in Irish, but the interrogative particle (and other question words), if present, comes before the verb. The next word, 'féidir', however, is not a verb: it is a noun meaning 'ability, possibility'. You can see where this is going: instead of using a verb like can, we phrase the question in terms of the ability to do something. So, no verb involved here. But whose ability?

The next word is 'leat', which is an inflected preposition: it is the preposition 'le' ('with') in the second person singular (you).1 This is actually part of a possessive construction in Irish: Irish does not have a verb to have; one way (among many) to express possession is to say that the possessed thing is 'with' the possessor. So, 'you have the ability' translates as 'is féidir leat', meaning literally '(there) is ability with you'. When asking a question, though, the question word 'an' is added and the verb 'is' can be omitted. So, 'an féidir leat?' = 'is there ability with you?' = 'can you?'.

The next word is 'athbhreithniú'. This is a noun meaning 'review', the verbal noun corresponding to the verb 'athbhreithnigh' meaning 'to review'. A verbal noun is a noun describing the action denoted by a verb. This is similar to a gerund in English: for the verb to sing, there is the corresponding action of singing. There is an important difference between an English-style gerund and a Celtic-style verbal noun, though: while a gerund can take an object, as in "I like singing that song", a verbal noun cannot: instead, you have to phrase it as something akin to "I like the singing of that song", introducing the object with a genitive/possessive construction. To give another example, the verbal noun for the verb construct would be less like constructing ("constructing houses takes time") and more like construction ("the construction of houses takes time"). Irish does not have gerunds or infinitives: it does everything with verbal nouns.

The next word is 'a', and I don't really know what this little word is doing here, though I have some hunches.2 I will ignore it for now.

Finally, the last word is 'dhéanamh'. That's the verbal noun of 'déan', meaning to do. So the sentence is actually phrased in terms of doing a review, rather than reviewing directly.3 But even to do is presented as a verbal noun here, so it's actually the doing of a review.

So the full sentence:

An féidir leat athbhreithniú a dhéanamh?

if translated literally, would be:

Is there possibility with you of the doing of a review?

And since the verb is is omitted after the question particle, there is no verb (other than verbal nouns) in this sentence.

Nouns everywhere

Irish reliance on verbal nouns means that sentences tend to look much more nouny in Irish than in the average Indo-European language. But that's only one element of it. Irish uses nouns in many other constructions where we tend to expect verbs in European languages. States of mind seem to be particularly prone to be rendered as nouns rather than verbs in Irish. For instance (and with the help of Google Translate, so take these translations with a grain of salt):

- I like apples. → Is maith liom úlla. (lit. apples are good with me)

- I need a car. → Tá carr ag teastáil uaim. (lit. a car is at need from me)

- I hope she comes. → Tá súil agam go dtiocfaidh sí. (lit. there is hope at me that she will come)

- I desire it. → Is mian liom é. (lit. There is desire with me [of] it)

Some of these have verbal equivalents, but the noun form seems to be preferred.

Conclusion

The conclusion is that Irish, and Celtic languages in general, seem to love nouns far more than their non-Celtic Indo-European cousins. In the grand scheme of the world's languages, this may not be too weird: some languages are known to lean towards the verby side of things, so it should not come as too great a surprise that some lean towards nouns. Nevertheless, in the context of Indo-European languages, the Celtic family really seems to stand out in its penchant for nouniness.

_____

1 If you know Portuguese or Spanish, this is similar to how these languages have a special form of the preposition com/con (with) combined with the personal pronouns: comigo/conmigo (with me), contigo (with you), etc. The difference is that in Irish, every preposition has inflected forms for each person.

2 If I understand correctly, what we have here is a cleft sentence construction. A cleft sentence is when you turn a sentence like I wrote the book into it was me who wrote the book. Basically you bring a bit of the sentence into focus (in this case, me) by moving everything else into a subclause. English does this for emphasis (in our example, to emphasize it was me and not anyone else). Some languages, like Portuguese, regularly do this for questions: como é que eu chego no aeroporto? (lit. how is it that I arrive in the airport?). And in Irish this seems to be mandatory in a variety of situations I don't understand very well at all.

3 After I wrote this, I realized that that's because the original sentence lacks an object, which actually sounds weird even in English ("can you review what?"), so Translate probably rendered it as "doing a review" as a way to get rid of the missing object. If I enter "Can you review it?" instead, Translate gives "An féidir leat é a athbhreithniú?", without resorting to "dhéanamh".

Random remarks on Old Chinese type-A/type-B syllables

2019-09-25 22:06 -0300. Tags: lang, old-chinese, in-english

[Update (2023-07-25): This post has been translated into Mandarin Chinese (on Medium and Zhihu) by Lyn.]

Every now and then Academia.edu throws an interesting paper suggestion into my inbox. Today I got a paper titled A Hypothesis on the origin of Old Chinese pharyngealization, by Laurent Sagart and William Baxter (2016). [Note: the linked paper is a draft, not the final published article. I don't know if there is any difference in the content between the draft and the final version.]

This post contains some observations and impressions about the paper. I should note as a disclaimer that I'm not a specialist in Old Chinese at all; I'm just this random person on the internet who has read a bunch of papers and watched the videos of Baxter & Sagart's 2007 workshop I mentioned in a previous post. This post should be seen as my personal notes while trying to understand and thinking about this subject.

I have to say that despite being a huge fan of Baxter & Sagart's work, this paper did not convince me. In fact, it actually weakened a bit my previous belief in the B&S pharyngeal hypothesis. Anyway, here we go.

[P.S.: By the end of the post, I get re-convinced about the pharyngeal hypothesis. This post ended up very rambly.]

* * *

Old Chinese is traditionally reconstructed as having two types of syllables, called type A and type B. Type B syllables are characterized by having a /-j-/ medial in Middle Chinese; type A ones are characterized by the lack of such palatal medial. Traditional reconstructions (e.g., Karlgren's) reconstruct this /-j-/ back into Old Chinese. More recent reconstructions have put this in doubt, though.

These are some known facts about type A and type B syllables:

Type B reflexes in Middle Chinese have (what is believed to be) a palatal medial -j-, while type A don't.

There is evidence that type B was not palatalized back in Old Chinese. Evidence, according to Wikipedia, includes:

Type B syllables are used to transcribe foreign words without a palatal medial;

The modern Min reflexes and presumed Tibeto-Burman cognates don't have a palatal medial;

- [Min is the only branch of modern Sinitic languages believed not to have descended from Middle Chinese, but rather to have split off earlier.]

"The fact that it is ignored in phonetic series."

- Most Chinese characters are composed of a semantic and a phonetic component. Characters with the same phonetic component generally have (in Old Chinese) the same rhyme and the same place of articulation of the initial. I understand this observation to mean that type A and type B syllables can be written with the same phonetic component, which would imply there is no distinction in rhyme or place of articulation of type A and type B syllables.

Type B syllables appear to be slightly more frequent than type A, which suggests that type B articulation was less marked than type A.

These are some post-Karlgren theories about the type A/B distinction:

-

Pulleyblank proposed a vowel length distinction, with A being short and B being long.

Starostin proposed the reverse: A being long and B being short.

This idea comes from a correlation between A/B type in Old Chinese words and vowel length in presumed cognates in Lushai, a Tibeto-Burman language of the Kuki-Chin group, with type A corresponding to long vowels and B to short ones.

It also has the benefit of assigning type B a less marked articulation than type A (which makes sense given that type B is slightly more frequent, see above).

Norman proposed pharyngealization as the distinguishing feature, with type A being pharyngealized and type B non-pharyngealized.

- His system actually contrasted plain, pharyngealized, and retroflex syllables; type B corresponds to plain syllables, and type A are either pharyngealized or retroflex in his system. Both pharyngealization and retroflexion blocked palatalization.

-

Similarly, Baxter & Sagart treat type A as pharyngealized, and type B as plain. Unlike Norman, B&S do not consider retroflex as a third type; they consider retroflexion as the effect of a medial /-r-/ in Old Chinese, which can occur with both type A and type B syllables.

Back in 2007 (at the B&S workshop), B&S notated type A syllables by doubling the initial, as a way to indicate them without committing to any particular realization (pharyngeal or otherwise), or to whether this was a feature of the initial or of the whole syllable. Norman considered pharyngealization to be a feature of the whole syllable, rather than the initial. B&S seems to have shifted towards considering it a feature of the initial; the paper in consideration here explicitly argues for pharyngealization to be a feature of the initial, coming from previous /Cʕ/ (consonant + pharyngeal) clusters. (The paper argues that "type-A and type-B syllables seem to rhyme with each other freely in Old Chinese poetry, which would be unexpected if pharyngealization was a feature of the rhyme as well as the onset". That is a good point, though it might just be that pharyngealization was not considered relevant in rhyming.)

In that system, every consonant has a plain and a pharyngealized version. At first sight, this looks a bit crazy, but that's not much different from, say, Irish having a palatalized and a velarized version of every consonant. There are some suspicious combinations, though; in particular, the pharyngealized glottal stop /ʔˤ/ does not look very convincing. It would not seem so problematic to me if pharyngealization were a feature of the syllable as a whole, since it would still be clearly articulated in the vowel; as a feature of the initial, it does not seem very likely.

The paper argues that these pharyngealized consonants come from pre-Old-Chinese /Cʕ/ clusters. The paper says these are clusters with a "pharyngeal fricative". One thing I just learned is that the /ʕ/ symbol can be used for either a pharyngeal fricative or an approximant; I only knew the approximant usage.

The paper further argues that these clusters come from previous CVʕV- syllables, i.e., the development was of the form:

nuʕup > nʕup > nˤup

It argues then that the corresponding long/short distinction in Lushai comes from the loss of the middle /ʕ/ and subsequent fusion of the identical vowels.

This is motivated by parallel developments in Austronesian and Austroasiatic. Proto-Austronesian seems to have had a constraint against single-syllable words: whenever a single-syllable CVC root would appear by itself (without affixes), it would surface as CV(ʔ)VC instead, with a long vowel 'interrupted' by a glottal stop, as a way to enforce the two-syllable constraint. The paper proposes the same constraint was present in a language ancestral to Proto-Sino-Tibetan. (It does not explicitly claim that this ancestral language would be the parent of Proto-Sino-Tibetan and Austronesian and Austroasiatic.) Syllables of the CV(ʔ)VC or CV(ʕ)VC type would then lead to pharyngealized, type A syllables in Old Chinese on the one hand, and long vowels after loss of the mid-consonant in Lushai.

I'm not very convinced by this idea. For one, there is no direct evidence for the /ʕ/ phoneme in Sino-Tibetan as far as I know. Of course, this was the same argument used against the laryngeal hypotheses in Proto-Indo-European during Saussure's lifetime, until Hittite was discovered which did partially preserve a laryngeal phoneme. The same could be true of the posited /ʕ/ phoneme. I'm not sure the case for /ʕ/ in Proto-Sino-Tibetan is as strong, though.

We are trying to account for a length distinction on one side, and type A/B on the other. Paper footnote 4 says: "Starostin accounted for the correlation by reconstructing a parallel length distinction for Old Chinese long vowels in type A and short vowels in type B. While this reconstruction makes sense of the apparent correlation with Lushai, there is no direct Chinese evidence for it, and it does not help explain the Hàn-time sound changes described above, which affected type A and type B differently."

The first thing to note is that there is no direct Chinese evidence for pharyngealized consonants either. Now for the Hàn-time sound changes referenced. I quote:

Inspired by the treatment in Norman (1994), Baxter and Sagart (2014) assign pharyngealization to OC type-A words, and absence of pharyngealization to type-B words. The main argument for reconstructing pharyngealization is a set of sound changes that occurred during the Hàn period (206 BCE – 220 CE), which affected type-A syllables and type-B syllables differently: original high vowels remain high in type-B syllables, but are lowered in type-A syllables; and original low vowels, which are raised in certain environments in type-B syllables, remain low in type-A syllables. Also, initial consonants often underwent palatalization in type-B syllables, but escaped such palatalization in type-A syllables. Reconstructing pharyngealization in the onset of type-A syllables seems to provide a plausible explanation for these differences, more so than any of the alternative proposals.1

Let's summarize the first part:

- High vowels are sometimes lowered in type A (e.g., /i/ > /e/);

- Low vowels are sometimes raised in type B (e.g., /e/ > /i/).

If we interpret A/B type as length, we would say that long vowels are lowered, and short vowels are raised. Would it be too crazy to consider length itself as the influencing factor? Vulgar Latin has also shifted vowels based on length; however, Vulgar Latin shows the opposite development: it is the short vowels that get lowered. Moreover, type A (i.e., long) prevents palatalization. Here we could perhaps make a better parallel to Vulgar Latin, where short /e/, /o/ become diphthongized /je/, /we/ (< /wo/) in Spanish. However, type B syllables palatalize regardless of the vowel, so the parallel breaks down again. Maybe B&S is right about pharyngealization after all.

The above quote has a footnote:

Moreover, at least one Hàn-dynasty commentator describes the difference between a type-A syllable and a type-B syllable by stating that the type-A syllable is “inside and deep” (nèi ér shēn 內而深), while the type-B syllable is “outside and shallow” (wài ér qiǎn 外而淺); “inside and deep” seems a natural way to describe the retraction of the tongue root that characterizes pharyngealization. See Baxter & Sagart (2014:72–73).

At the same time, Wikipedia has the following quote:

Pulleyblank initially proposed that type B syllables had longer vowels.[89] Later, citing cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages, Starostin and Zhengzhang independently proposed long vowels for type A and short vowels for type B.[90][91][92] The latter proposal might explain the description in some Eastern Han commentaries of type A and B syllables as huǎnqì 緩氣 'slow breath' and jíqì 急氣 'fast breath' respectively.[93]

It is hard to make sense of these ancient quotes. It also makes one contemplate how much information, small clues and indirect evidence is out there for reconstructing Old Chinese, and wonder how much an amateur like me can hope to grasp about this subject.

The paper finishes with a discussion of the correlation between Lushai length and Chinese A/B type. The whole argument of the paper hinges on there being such a correlation, so they decided to check how much evidence there is for the correlation. After filtering candidates to avoid problematic cases, they get to 43 comparanda in Proto-Kuki-Chin and Old Chinese, and present the following table:

PKC long PKC short Chinese type A 6 6 Chinese type B 5 26

They conclude that the correlation is statistically significant. One thing stands out to me, though: although PKC short and Chinese type B seem to strongly correlate, there does not seem to be a strong correlation at all between PKC long and Chinese type A, which is a bit disturbing. While this may be an effect of the small sample and the fact that there are more short (32) than long (11) words in the sample, and more type B (31) than type A (12), there may also be something meaningful going on here.

Let's interpret this table:

- Chinese type B corresponds to PKC short vowels 26/31 (~83%) of the time, and to long vowels 5/31 of the time. This looks like a suggestive correlation.

- Chinese type A corresponds to PKC short vowels 6/12 (50%) of the time, and to long vowels also 6/12 (50%) of the time. That looks like just chance.

One way to interpret this is that there is a feature in Proto-Sino-Tibetan (PST) whose presence triggers type B in Old Chinese and short vowels in PKC, but whose absence does not influence the syllable's type. This would turn type B the marked element again, which is unsatisfying, and would also turn short vowels the marked element, which is even less satisfying.

The correlation may be less direct. For example, it might be that PST had both length and pharyngealization (or something that yields length and pharyngealization as reflexes), but only long syllables could be pharyngealized. Then short PST syllables would yield PKC short and Chinese type B, but long syllables could get either type A or B. However, this would imply that long PST syllables don't always yield long PKC syllables. It might just be so, or it might be that the PST feature that enabled length and pharyngealization (or whatever was type A/B) distinctions was a third one, say, only syllables of a certain kind could carry those distinctions. The absence of that feature would yield type B and PKC short, but its presence enabled syllables to go either way.

Conclusions

The main argument of the paper is to show that long vowels interrupted by a pharyngeal element were the origin of both Old Chinese type A syllables (argued to have pharyngealized initials) and Lushai long vowels (after loss of the pharyngeal element). The fact that the correlation only seems to appear between short vowels and type B, but not long vowels and type A, suggests that long vowels and type A do not share a common origin, only perhaps a common enabling environment (i.e., they can occur in the same environments, but are distinct features, in Proto-Sino-Tibetan). In my opinion, this undermines the motivation for reconstructing /CVʕV-/ roots for Sino-Tibetan.

Pharyngealization still seems a compelling explanation for the phenomena observed with type A syllables. However, it is not clear to me there is any good reason to consider it a feature of the initial (like the article proposes) rather than the whole syllable (as in Norton's original proposal).

German declension: modifiers

2019-05-03 22:13 -0300. Tags: lang, german, in-english

I've been dabbling in German again, and trying to learn the declensions for the articles, adjectives and other modifiers. These are some notes I made in the process.

The tables below are colorized with JavaScript. If they don't get colorized properly for you, please notify me. If you find mistakes in the text, please notify me too.

Genders, cases and numbers

German has three genders (masculine, feminine, neuter), and two numbers (singular and plural). There is a single plural declension for all genders, so, for didactical purposes, we can think of plural as a fourth gender.

German has four cases (nominative, accusative, dative, genitive), which indicate the role of the noun phrase in the sentence. In general lines:

- Nominative is used for the subject of the sentence (the dog sees the cat). It is also the 'default' form of nouns you will find in the dictionary.

- Accusative is used for the object of the sentence (the dog sees the cat).

- Dative is used for the indirect object of the sentence (the boy gave the girl a book).

- Genitive is used for possessives (the girl's book) and similar situations of nouns modifying nouns.

All cases but the nominative are also used as objects of certain prepositions. Each preposition defines which case it wants its object to appear in. Spatial prepositions typically take the dative to indicate place and the accusative to indicate movement:

- Dative: im Wald (= in dem Wald) "in the forest"

- Accusative: in den Wald "into the forest"

In the tables in this text, genders will appear in the order masculine, neuter, feminine, plural. This is not the usual order they are presented, but masculine and neuter often have similar forms, and so do feminine and plural. I chose this order to leave similar forms close to each other. The order of cases was also chosen for similar reasons.

The definite article

The definite article forms in the nominative are: masculine der, neuter das, feminine die, plural die. It took me a while to memorize which gender is which form, until I realized:

- der is similar to er (he).

- die is similar to sie (she).

- die can also be plural, and so can sie (they).

- das ends in -s like es (it). It is also cognate to English that and the Icelandic third person neuter pronoun það. (I realize that a comparison to Icelandic is not exactly the best mnemonic device in the world, but it works for me.)

The declined forms are:

| Masc. | Neut. | Fem. | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | der | das | die | die |

| Acc. | den | das | die | die |

| Dat. | dem | dem | der | den |

| Gen. | des | des | der | der |

There are a lot of patterns to observe here, and they will often apply to other parts of the declension system too:

- Masculine is the only gender that distinguishes nominative from accusative; the other genders always have the same form for both.

- Masculine and neuter have the same dative and the same genitive.

- Feminine uses one single form for the nominative and accusative, and another single form for dative and genitive.

- German has a general fixation with the idea of having an -n in the dative plural. This applies to nouns too (e.g., den Kindern "to the children"), except nouns whose plural ends in -s like Autos. Other than that, the article is the same for feminine and for plural.

The indefinite article (ein)

At this point I would like to present the declension for the indefinite article (ein). The problem is that it does not have a plural, so the table would not show all the forms I want to show. Instead, I will present the declension table for kein, which is the same except it has a plural.

| Masc. | Neut. | Fem. | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | kein | kein | keine | keine |

| Acc. | keinen | kein | keine | keine |

| Dat. | keinem | keinem | keiner | keinen |

| Gen. | keines | keines | keiner | keiner |

Many of the patterns repeat themselves here.

- Masculine is the only gender with distinct nominative and accusative forms.

- The masculine nominative has no ending, but the endings for the other cases are the same as those of the definite article (accusative -en, dative -em, genitive -es).

- The neuter nominative has no ending either (and neither does the accusative; remember that the genders other than masculine don't distinguish nominative and accusative), but the dative and genitive are again like the definite article, and the same as the masculine.

- The endings for feminine and plural are also similar to the definite article: feminine has -e in nominative and accusative, -er in dative and genitive. Dative plural again has its characteristic -n, but otherwise it's the same as the feminine.

There are three places in the table where kein has no ending: the masculine nominative and the neuter nominative and accusative. These three places will be important later.

Adjectives

German adjectives have three different kinds of declension:

- The strong declension is used when the adjective is not preceded by an article or other determiner.

- The weak declension is used when the adjective is preceded by the definite article.

- The mixed declension is used when the adjective is preceded by the indefinite article and the possessive determiners (mein, etc.).

In the following tables, we will use the adjective groß (big, large) as an example.

Strong declension

| Masc. | Neut. | Fem. | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | großer | großes | große | große |

| Acc. | großen | großes | große | große |

| Dat. | großem | großem | großer | großen |

| Gen. | großen | großen | großer | großer |

The endings look a lot like those of the indefinite article, with some important differences.

- Remember those three places where kein had no ending? In these places, the strong adjective declension has the same endings as the definite article:

- großer (like der) in the masculine nominative,

- großes (like das) in the neuter nominative/accusative.

The other difference is that the masculine and neuter genitive ending is -en, not -es.

Otherwise, all the patterns repeat themselves here.

Weak declension

The weak declension is used with the definite article. Actually, to quote Wikipedia, "weak declension is used when the article itself clearly indicates case, gender, and number". It is used not only with the definite article, but also with other determiners like welcher (which), solcher (such), dieser (this), aller (all).

| Masc. | Neut. | Fem. | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | der große | das große | die große | die großen |

| Acc. | den großen | das große | die große | die großen |

| Dat. | dem großen | dem großen | der großen | den großen |

| Gen. | des großen | des großen | der großen | der großen |

Most of the endings are -en in the weak declension. The exceptions (which have -e instead) are:

- The same three places where kein has no ending: the masculine nominative and neuter nominative and accusative.

- Masculine always has distinct forms for nominative and accusative, so that's not much of a surprise.

- The feminine nominative and accusative. The feminine always has one form for nominative and accusative, and one form for the dative and genitive.

Mixed declension

The mixed declension is used with the indefinite article and the possessive determiners.

| Masc. | Neut. | Fem. | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | ein großer | ein großes | eine große | keine großen |

| Acc. | einen großen | ein großes | eine große | keine großen |

| Dat. | einem großen | einem großen | einer großen | keinen großen |

| Gen. | eines großen | eines großen | einer großen | keine großen |

The mixed declension is identical to the weak declension, except at those three places where kein has no ending: masculine nominative and neuter nominative and accusative. In those places, it has the strong declension endings instead (-er for masculine nominative, and -es for neuter nominative and accusative).

You can think of it as the adjective having the strong endings to compensate for the lack of endings of the article in those cases, e.g., because masculine nominative ein has no ending, the großer following it gets more distinctive endings.

Trivia etymologica #4: puxar, push, empurrar

2019-02-08 01:27 -0200. Tags: lang, etymology, em-portugues

Pois já fazia um tempo que eu andava intrigado com as palavras puxar, push e empurrar:

![[Imagem: Instruções de saída de emergência de ônibus. Português: 'Saída de emergência: Puxe a alavanca e empurre a janela'. Espanhol: 'Salida de emergencia: Tire y empuje la ventana'. Inglês: 'Emergency exit: Pull down the lever and push the window'.]](img/push-puxar.jpg)

A fonte de todo o questionamento

push e puxar, como sabemos, significam coisas opostas, e sempre constam nas listinhas de "false friends" entre o português e o inglês. A semelhança entre essas palavras é um tanto surpreendente, mas a princípio poderia ser apenas coincidência.

Por outro lado, empuxo é algo que empurra (= pushes).

Finalmente, empurrar em espanhol é empujar. Essa correspondência entre rr em português e j em espanhol não é regular, e só faria sentido se a palavra tivesse sido importada de uma das línguas para a outra (e não herdada diretamente do latim por ambas), depois de o j do espanhol e o rr do português terem adquirido sons similares.

Pois acontece, imaginem vocês, que todas essas palavras são cognatas.

puxar vem do latim pulso, pulsare, que significa, entre outras coisas, "empurrar". (Da mesma raiz derivam também impulso, expulso, propulsão, repulsa, além de, obviamente, pulsar.) Em algum momento, a palavra inverteu de sentido até chegar no português; quando e como isso aconteceu fica sugerido como exercício para o leitor. A mesma palavra dá origem em espanhol à palavra pujar, que significa "fazer esforço, empurrar", entre outros sentidos.

De impulso, impulsare (in + pulsare) deriva a palavra empujar em espanhol. Aparentemente a palavra empuxar também existe em português, de onde deriva empuxo, com o signficado original de algo que empurra. Não contente com o vocábulo nativo, entretanto, o português posteriormente importa o empujar do espanhol como empurrar.

Finalmente, push é derivado do francês medieval pousser, do francês antigo poulser, do latim pulsare. Assim, embora push e puxar possam ser falsos amigos, elas são tecnicamente cognatos verdadeiros, sendo puxar talvez o irmão gêmeo maligno da família.

Old Chinese and related resources

2018-12-30 22:35 -0200. Tags: lang, in-english

This post collects some links to resources about Old Chinese I have found on the web. Maybe I will move these to a page of their own, as soon as I figure out how I want to organize the non-blog parts of this website.

Texts

- Wikipedia: Reconstructions of Old Chinese.

- Wikibooks: Character List for Karlgren's GSR, an index of characters grouped by phonetic component according to Karlgren's Grammata Serica Recensa. Many Wiktionary entries for Chinese characters also contain phonetic series information.

Short videos

- NativLang: What "Ancient" Chinese Sounded Like - and how we know. The video is mostly about Middle Chinese reconstruction, but gives a nice overview of what reconstruction of older stages of Chinese is all about.

- Ancient Voices, a YouTube channel with reading of poems in Old Chinese reconstructed pronunciation. (The reconstructions seem to be a version of Baxter-Sagart, given the abundance of /ˤ/s, but with a somewhat simplified notation.)

- The Sound of the Old Chinese Language (Numbers & The Book of Songs). The poem actually comes from the Ancient Voices channel, but is read in a faster, more natural pace; the /ˤ/s seem to be pronounced as /ʔ/, though.

- Sinitic historical phonology, video (and commentary on Language Log) with a single Chinese poem read in various reconstructed stages of the language, as well as in modern Mandarin. Unlike the above videos, the Old Chinese pronunciations sound really awkward, but the video is interesting for the variety of language stages represented.

Books

- William Baxter. A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. 1992.

- William Baxter, Laurent Sagart. Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction. 2014.

Workshops

Summer School in Old Chinese Phonology, 2007

These are videos of a 3-day workshop with presentations by Baxter and Sagart.

- The Baxter-Sagart System of Old Chinese Reconstruction 2007-07-02 (mp4)

- Old Chinese Word Structure 2007-07-02 (mp4)

- Onsets 2007-07-03 (mp4)

- Finals 2007-07-03 (mp4)

- Lines of Evidence 2007-07-04 (mp4)

- Sino-Tibetan and Beyond 2007-07-04 (mp4)

Recent Advances…

- Recent Advances in Old Chinese Historical Phonology, 2015 (playlist).

- Recent Advances in Tangut Studies, 2017 (playlist).

Trivia etymologica #3: -ães, -ãos, -ões

2017-08-17 13:29 -0300. Tags: lang, etymology, em-portugues

Em português, palavras terminadas em -ão têm três possíveis terminações de plural diferentes: -ães (cão → cães), -ãos (mão → mãos) e -ões (leão → leões).

Como é que pode isso?

Esse é mais um caso em que olhar para o espanhol pode nos dar uma idéia melhor do que está acontecendo. Vamos pegar algumas palavras representativas de cada grupo e ver como se comportam os equivalentes em espanhol:

| Singular | Plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Português | Espanhol | Português | Espanhol | |

| -ães | cão | can | cães | canes |

| capitão | capitán | capitães | capitanes | |

| alemão | alemán | alemães | alemanes | |

| -ãos | mão | mano | mãos | manos |

| irmão | hermano | irmãos | hermanos | |

| cidadão | ciudadano | cidadãos | ciudadanos | |

| -ões | leão | león | leões | leones |

| nação | nación | nações | naciones | |

| leão | león | leões | leones | |

O que nós observamos é que em espanhol, cada grupo de palavras tem uma terminação diferente tanto no singular (-án, -ano, -ón) quanto no plural (-anes, -anos, -ones), enquanto em português, todas têm a mesma terminação no singular (-ão), mas terminações distintas no plural (-ães, -ãos, -ões). A relação entre as terminações no plural em espanhol* e português é bem direta: o português perdeu o n entre vogais (como já vimos acontecer no episódio anterior), mas antes de sair de cena o n nasalizou a vogal anterior, i.e, anes → ães, anos → ãos, ones → ões.

Já no singular, as três terminações se fundiram em português. O que provavelmente aconteceu (e eu preciso arranjar mais material sobre a história fonológica do português) é que o mesmo processo de perda do n + nasalização ocorreu com as terminações do singular (i.e., algo como can → cã, mano → mão, leon → leõ), e com o tempo essas terminações se "normalizaram" na terminação mais comum -ão. Como conseqüência, o singular perdeu a distinção entre as três terminações, enquanto o plural segue com três terminações distintas.

_____

* Tecnicamente eu não deveria estar partindo das formas do espanhol para chegar nas do português, mas sim partir da língua mãe de ambas, i.e., o dialeto de latim vulgar falado na Península Ibérica. Porém, nesse caso em particular o espanhol preserva essencialmente as mesmas terminações da língua mãe, então não há problema em derivar diretamente as formas do português a partir das do espanhol.

Trivia etymologica #2: cheio, full

2017-03-13 00:17 -0300. Tags: lang, etymology, em-portugues

Seguindo o tema de fartura do último episódio, começaremos nosso passeio etimológico de hoje com a palavra cheio. Cheio vem do latim plenus. É uma mudança fonética e tanto, então vamos por partes.

O meio

Cheio em espanhol é lleno. Olhar para o espanhol freqüentemente ajuda a entender a etimologia de uma palavra em português, porque o espanhol conserva alguns sons que se perderam em português, e vice-versa. Neste caso, o espanhol conservou o n de plenus que o português perdeu. O português tem uma séria mania de perder os sons l e n entre vogais do latim. Exemplos:

- Latim luna > espanhol luna, português lua;

- Latim bona > espanhol buena, português boa;

- Latim molere > espanhol moler, português moer;

Quando as vogais antes e depois do l ou n deletado são iguais, o português junta as duas numa só:

- Latim color > espanhol color, português cor;

- Latim dolor > espanhol dolor, português dor;

E entre certos encontros de vogais (aparentemente entre ea e entre eo), o português prefere inserir um i (produzindo eia, eio):

- Latim plenus > espanhol lleno, português cheio;

- Latim cena > espanhol cena, português ceia;

Por outro lado, quando o l ou n era geminado em latim, isto é, ll e nn, ele é mantido como l e n em português. Já em espanhol, o som resultante do ll do latim continua sendo escrito como ll, mas é pronunciado como o lh do português (com variações dependendo do dialeto), e o nn do latim se torna o ñ do espanhol (pronunciado aproximadamente como o nh do português). Exemplos:

- Latim bellus > português belo, espanhol bello;

- Latim vulgar ingannare > português enganar, espanhol engañar;

O início

A outra diferença entre cheio e lleno é o som inicial. Nesse caso, nem o português nem o espanhol conservaram o som original do latim, mas pl e cl quase sempre viram ch em português e ll em espanhol. Outros exemplos:

- Latim clavis > português chave, espanhol llave;

- Latim clamare > português chamar, espanhol llamar;

- Latim pluvia > português chuva, espanhol lluvia;

- Latim plorare > português chorar, espanhol llorar;

Provavelmente havia alguma peculiaridade na pronúncia desses encontros em latim (ou pelo menos em alguns dialetos de latim), porque eles sofrem modificações em diversas outras línguas românicas também; em particular, em italiano as palavras acima são chiave (o ch tem som de k), chiamare, pioggia e piorare. No geral, o que se observa é uma palatalização desses encontros consonantais: a pronúncia deles tendeu a evoluir para um ponto de articulação mais próximo do palato (céu da boca). Meu palpite é que o l nesses encontros tinha um som mais próximo do nosso lh nesses dialetos (i.e., /klʲavis, plʲuvia/ (algo como clhávis, plhúvia)).

Surpreendentemente, o francês, que costuma ser uma festa de mudanças fonéticas, mantém ambos os encontros intactos (clef, clamer, pluie, pleurer).

Mudanças regulares

Ok. Como vimos, plenus do latim se torna cheio em português. O que vimos são duas mudanças fonéticas regulares na história do português: uma mudança de pl inicial para ch, e uma perda de n entre vogais. No geral, as mudanças de pronúncia que ocorrem ao longo da história de uma língua têm essa natureza regular: elas afetam certos sons em todas as palavras da língua, sempre que eles ocorrem em determinadas circunstâncias. Claro que como com toda regra, ocasionalmente há exceções, por diversos motivos, mas no geral se espera essa regularidade quando se está formulando uma regra que explique a relação entre duas línguas aparentadas (no caso, latim e português).

Mas espera um pouco, você me diz: o português também possui a palavra pleno (e plenitude), que apresenta tanto o pl inicial quanto o n intervocálico original de plenus. Como é que pode isso?

A resposta nesse caso é que pleno é uma palavra reimportada do latim, depois que esses sound shifts já tinham acontecido. O português (e demais línguas românicas, bem como o inglês) contêm inúmeras palavras desse tipo, tipicamente reintroduzidas a partir da época do Renascimento, quando a cultura clássica grega e romana entrou em alta novamente. O resultado é que freqüentemente o português tem duas versões de uma mesma palavra latina: uma herdada naturalmente do latim, passando pelas mudanças de pronúncia históricas da língua, e uma reimportada diretamente do latim, sem a passagem por essas mudanças. Tipicamente, essas palavras reintroduzidas têm um tom mais formal, enquanto as versões "nativas" têm um tom mais coloquial. Exemplos são cheio e pleno, (lugar) vago e vácuo, chave e clave, paço e palácio. Outras vezes o português tem uma palavra nativa, herdada do latim e passando pelas mudanças fonéticas esperados, e diversas palavras relacionadas importadas posteriormente do latim sem essas mudanças. Exemplos são vida (do latim vita) e vital; chuva (do latim pluvia) e pluvial; mês (do latim mensis) e mensal.

Ok, plenus

Vamos voltar para o latim. Plenus em latim significa – adivinhem só – cheio. Em latim também há um verbo relacionado, pleo, plere, que significa encher. O particípio desse verbo é pletus, que, combinado com a típica variedade de prefixos, nos dá palavras como repleto, completo (e, em inglês, deplete). De in- + plere obtemos implere, que é a origem de encher. De sub- + pleo obtemos supplere, de onde vem suprir (e supply, e suplemento). De com/con- + pleo obtemos complere, de onde vem cumprir (além de completo, e complemento).

Em última instância, pleo vem da raiz indo-européia *pleh₁. Outras palavras dessa mesma raiz são plus (e duplus, triplus, etc.) e polys em grego (de onde vem o nosso prefixo poli-).

Há muitas mil eras eu falei por aqui sobre a Lei de Grimm, que descreve a evolução de alguns sons do proto-indo-europeu nas línguas germânicas. Como visto lá, o p do proto-indo-europeu corresponde ao f nas línguas germânicas. E sure enough, full e fill vêm da mesma raiz *pelh₁ que nos dá pleno e cheio. Viel do alemão também vem da mesma raiz. (Esse v se pronuncia /f/. Curiosamente, o alemão vozeou o /f/ para /v/ antes de vogais na Idade Média e shiftou ele de volta para /f/ alguns séculos depois.)

E a essa altura, já estamos todos cheios do assunto.

Trivia etymologica #1: much vs. mucho

2017-03-05 01:43 -0300. Tags: lang, etymology, em-portugues

Há muitos mil anos, explicando para alguém a diferença entre muy e mucho em espanhol, eu fiz uma analogia com o inglês: muy é como very em inglês, e modifica adjetivos e advérbios, e.g., muy rápido = very fast. Já mucho é como many em inglês, e modifica substantivos: muchas cosas = many things. Na verdade essa explicação é parcialmente correta: muchos no plural é como many, e é usado para substantivos contáveis (como em muchas cosas). Mas mucho no singular é como much, e é usado para substantivos não-contáveis, e.g., mucho dinero = much money.

Na época eu me perguntei: será que much e mucho são cognatas? Apesar da similaridade de som e significado, seria pouco provável que as duas palavras fossem cognatas (a menos que o inglês tivesse importado a palavra do espanhol, o que também seria pouco provável). Isso porque se houvesse uma raiz indo-européia comum para as duas palavras, ela teria passado por mudanças fonéticas diferentes no caminho até o inglês e até o espanhol, e seria pouco provável que o resultado final se parecesse tanto em ambos os branches.

As it turns out, as palavras realmente não são cognatas. much vem do inglês médio muche, muchel, do inglês antigo myċel, miċel. O ċ (som de "tch", ou /tʃ/ em IPA) do Old English é resultado de um shift de /k/ para /tʃ/ diante de /e/ e /i/. Assim, a palavra original era algo como /mikel/, que, em última instância, vem da raiz indo-européia *méǵh₂-, que significa 'grande'. É a mesma raiz de mega em grego, e de magnus em latim. *méǵh₂- com o sufixo *-is, *-yos resulta em latim nas palavras magis, que é a origem da palavra mais em português, e maior, que é a origem de (quem imaginaria?) maior em português. Resumindo, much, mega, mais e maior são todas cognatas.

Mucho, por outro lado, assim como o muito do português, vem do latim multus, que é também a origem do prefixo multi e de palavras como múltiplo. Segundo nosso amigo Wiktionary, multus vem da raiz indo-européia *mel-, e é cognata de melior (de onde vem melhor), que nada mais é do que *mel- com o mesmo sufixo *-yos que transforma mag(nus) em magis e maior.

Por fim, muy é uma contração do espanhol antigo muito, cuja derivação é trivial e sugerida como exercício para o leitor.

And so it goes

2016-07-15 14:40 -0300. Tags: music, lang, em-portugues

Fazia muitos mil kalpas que eu queria achar a letra em cantonês da música tema do filme Tai Chi Master (太極張三豐). No fim consegui achar vendo um pedaço do filme com legendas em chinês, transcrevendo parte da legenda e procurando nas interwebs. A letra veio daqui, e a transcrição em Jyutping daqui. (As transcrições em vermelho são as que eu corrigi conferindo no Wiktionary as que eu achava que estavam erradas.) Aqui tem uma versão com legendas em inglês do trecho da música que aparece no filme, mas não sei quão confiável é a legenda.

| zi6 | seon3 | sau2 | zung1 | bat1 | gin3 | goeng6 | jyu4 | ging3 |

| 自 | 信 | 手 | 中 | 不 | 見 | 強 | 與 | 勁 |

| zi6 | jau5 | sam1 | zung1 | jat1 | pin3 | wo4 | jyu4 | peng4 |

| 自 | 有 | 心 | 中 | 一 | 片 | 和 | 與 | 平 |

| jik6 | loi4 | seon6 | sau6 |

| 逆 | 來 | 順 | 受 |

| hung1 | heoi1 | gin3 | fung1 | sing4 |

| 空 | 虛 | 見 | 豐 | 盛 |

| kong4 | bou6 | faa3 | sing1 | peng4 |

| 狂 | 暴 | 化 | 升 | 平 |

| mou4 | lou6 | cyu2 | zi6 | jau5 | tin1 | meng6 |

| 無 | 路 | 處 | 自 | 有 | 天 | 命 |

| dung6 | deoi3 | zing6 |

| 動 | 對 | 靜 |

| ceoi4 | deoi3 | sing4 |

| 除 | 對 | 乘 |

| ceoi4 | jyun4 | jap6 | sai3 |

| 隨 | 緣 | 入 | 世 |

| jan1 | fung1 | ceot1 | sai3 |

| 因 | 風 | 出 | 世 |

| mou4 | cing4 | jik6 | jau5 | cing4 |

| 無 | 情 | 亦 | 有 | 情 |

| ceoi4 | jyun4 | seon6 | sing3 |

| 隨 | 緣 | 順 | 性 |

| bat1 | caang1 | bat1 | sing1 |

| 不 | 爭 | 不 | 勝 |

| mou4 | cing4 | si6 | jau5 | cing4 |

| 無 | 情 | 是 | 有 | 情 |

* * *

| daan6 | gaau3 | hau2 | zung1 | bat1 | syut3 | ci4 | jyu4 | lim1 |

| 但 | 覺 | 口 | 中 | 不 | 說 | 辭 | 與 | 令 |

| daan6 | gin3 | sau2 | zung1 | nim1 | gwo1 | can4 | sai3 | cing4 |

| 但 | 見 | 手 | 中 | 拈 | 過 | 塵 | 世 | 情 |

| wui6 | joeng4 | gap3 | jam1 |

| 匯 | 陽 | 合 | 陰 |

| sam1 | ngon1 | gaau3 | tin1 | zing6 |

| 心 | 安 | 覺 | 天 | 靜 |

| jau4 | joek6 | gaau3 | fung1 | peng4 |

| 柔 | 弱 | 覺 | 風 | 平 |

| mou4 | lou6 | cyu2 | zi6 | jau5 | tin1 | meng6 |

| 無 | 路 | 處 | 自 | 有 | 天 | 命 |

| dung6 | deoi3 | zing6 |

| 動 | 對 | 靜 |

| ceoi4 | deoi3 | sing4 |

| 除 | 對 | 乘 |

| ceoi4 | jyun4 | jap6 | sai3 |

| 隨 | 緣 | 入 | 世 |

| jan1 | fung1 | ceot1 | sai3 |

| 因 | 風 | 出 | 世 |

| mou4 | cing4 | jik6 | jau5 | cing4 |

| 無 | 情 | 亦 | 有 | 情 |

| ceoi4 | jyun4 | seon6 | sing3 |

| 隨 | 緣 | 順 | 性 |

| bat1 | caang1 | bat1 | sing1 |

| 不 | 爭 | 不 | 勝 |

| mou4 | cing4 | si6 | jau5 | cing4 |

| 無 | 情 | 是 | 有 | 情 |

Ensinando inglês

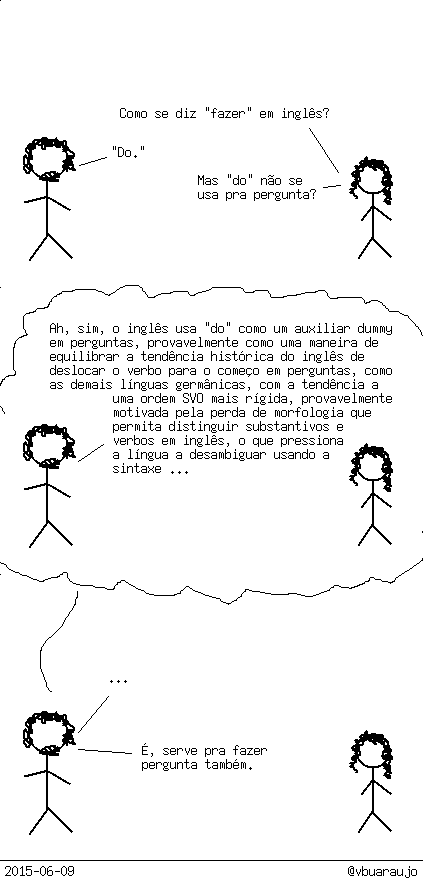

2015-06-09 23:28 -0300. Tags: lang, comic, img, random, em-portugues

Baseado em fatos reais.

(E eu ia mudar o texto para "distinguir substantivos e verbos facilmente em inglês", mas já gastei meu estoque de paciência com o GIMP hoje.)